Sluggishly reacting applications, latency in almost everything you do, crashes, blank screens, long lag to pick up networks, buggy settings. Do you remember any of this? Sounds like some old-fashioned feature phone that was somewhat overloaded by its ambitious maker, doesn’t it? But, alas, no, it is not. This is the user experience with a one-year-old iPhone 3G, 16GB since 24 June 2010. Do you recognise the date? Then luck will have it that you have experienced the same: the grandly titled “iOS4” update that was being pushed down your throat (or rather iTunes) to your iPhone 3G.

Sluggishly reacting applications, latency in almost everything you do, crashes, blank screens, long lag to pick up networks, buggy settings. Do you remember any of this? Sounds like some old-fashioned feature phone that was somewhat overloaded by its ambitious maker, doesn’t it? But, alas, no, it is not. This is the user experience with a one-year-old iPhone 3G, 16GB since 24 June 2010. Do you recognise the date? Then luck will have it that you have experienced the same: the grandly titled “iOS4” update that was being pushed down your throat (or rather iTunes) to your iPhone 3G.

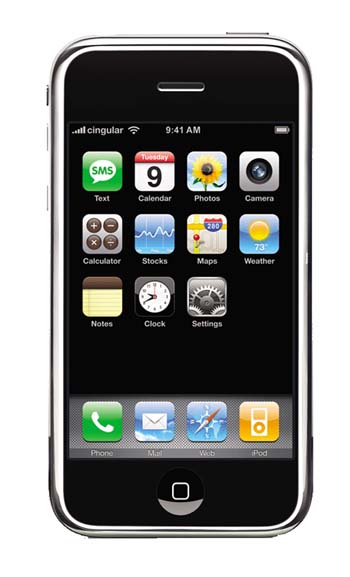

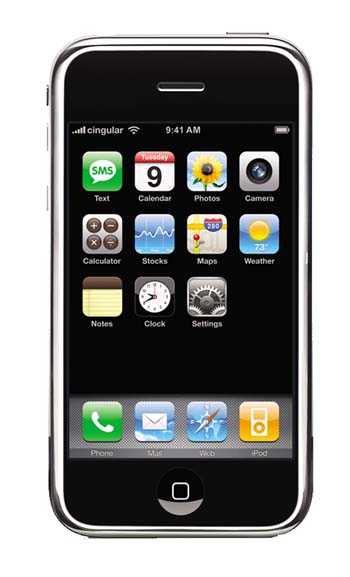

Apple has been hailed for poking everyone else making handsets in the eye when it came out with the iPhone: here is a newbie that got it all right and venerable industry leaders found themselves with cartons full of ostrich egg on their faces: here was someone who got it all right: combining great build quality, maybe only OK-ish specs and unsurpassed UI with a vertically integrated publishing and distribution system that made for a leap in usage of mobile devices. It was a bad slap for the Nokias etc of this world and a revelation for millions of users (even if they were not Apple fanboys).

Software and hardware need to blend well

And then it came back to bite them! I am not a techie but iOS4 on the iPhone 3G feels like someone put a little too much luggage onto too frail a porter: the things creaks and aches at every corner. Gone are the days where one could switch from one app to another in seconds, where the iPhone – in good Apple style – did what you wanted it to do without much ado but breathtaking efficiency and speed. Now, it is clunky and, well, very old-fashioned. It could of course all have been avoided: just don’t push iOS4 to the iPhone 3G (or older models). No one would have cried, you should think: if the hardware cannot handle it, it cannot handle it. Users understand such things one should think. Keep iOS4 to the iPhone 4 (even the numbers match, doh!).

And then it came back to bite them! I am not a techie but iOS4 on the iPhone 3G feels like someone put a little too much luggage onto too frail a porter: the things creaks and aches at every corner. Gone are the days where one could switch from one app to another in seconds, where the iPhone – in good Apple style – did what you wanted it to do without much ado but breathtaking efficiency and speed. Now, it is clunky and, well, very old-fashioned. It could of course all have been avoided: just don’t push iOS4 to the iPhone 3G (or older models). No one would have cried, you should think: if the hardware cannot handle it, it cannot handle it. Users understand such things one should think. Keep iOS4 to the iPhone 4 (even the numbers match, doh!).

Allowing iOS4 to be pushed to the iPhone 3G was one horrendous mistake!

So is this the latest marketing trick of Apple? Go and spend another £600 to buy a new one, you say? This would be utter and incredible cynicism on a scale that would put Apple right on top of the current bad-boy scale! After all, I am not talking about an old, well-worn something-or-other device; I am talking about something that was only a year ago (which is short in terms of device replacement even in the mobile space) for a considerable amount of money!

However, I think that is not it. My suspicion is rather more frightening. It very much feels like Apple starting to overextend itself and learn how complex and fragile it is to deal in the mobile space. Pushing iOS4 to devices that obviously (not only under some special and hard to find circumstances) cannot cope with it is just shoddy. Every game or app developer in the market for more than 2 years would have caught this in QA. Does Apple not have QA? Or not anymore? Or at least not enough? It might happen to you when you try too much too quickly. Apple’s passion (or paranoia?) that drives it to try and do everything itself appears to haunt it now: I mean, QA is really simple. You don’t need cohorts of phDs in elementary physics to do this. It doesn’t take you 3 years to build it up. And – last but not least – Apple appeared to being very much on top of this in the past. So what happened?

However, I think that is not it. My suspicion is rather more frightening. It very much feels like Apple starting to overextend itself and learn how complex and fragile it is to deal in the mobile space. Pushing iOS4 to devices that obviously (not only under some special and hard to find circumstances) cannot cope with it is just shoddy. Every game or app developer in the market for more than 2 years would have caught this in QA. Does Apple not have QA? Or not anymore? Or at least not enough? It might happen to you when you try too much too quickly. Apple’s passion (or paranoia?) that drives it to try and do everything itself appears to haunt it now: I mean, QA is really simple. You don’t need cohorts of phDs in elementary physics to do this. It doesn’t take you 3 years to build it up. And – last but not least – Apple appeared to being very much on top of this in the past. So what happened?

A great showcase on the importance of User Experience

I have been throwing this into the faces of Nokia lovers who never fail to point out how technically superior Nokia’s hardware is: users do not give a toss about hardware specs. They care for the overall user experience. The unhappy marriage of the 3G with iOS4 shows what this does when it goes wrong: all the fun of using an iPhone is gone. What good is it when my phone lets me down every 10 minutes? What fun if my e-mail doesn’t open for 20 seconds? How exciting if applications appear to be frozen only to open just seconds after I pressed the home button (that will kill them just in time after I saw that it did, at the end, react)? Utter frustration. Rotten user experience. Complete fail.

Apple shows us, hence, accidentally how important the overall user experience is, and this may well be my final example on this: a simple (well, maybe not so simple) piece of software turns the most coveted consumer device of the day into a somewhat lame brick! However, it also shows how incredibly important it is to match the hardware (and network environment) to what the overall product (here: iOS4) promises to deliver (non-Apple case in hand would be video-calling on the Nokia N70 back in 2005: there was just no way this would work in practice; the experience was just too horrendous).

So, dear Apple, back to the drawing board. And if I may make a humble suggestion: just push the last pre-iOS4 version back to the older devices tomorrow! First thing! Promise! Please!

To all the others: this is a great opportunity! Catch up! Double your efforts! But don’t forget that the coolest frigging hardware (12 MP cameras anyone) is useless if the UX is not matching it either!

Back in summer last year (when there was a whole lot less rain), I looked at

Back in summer last year (when there was a whole lot less rain), I looked at Now, distinct to what old lore may have, users do not tend to care for technology much. They care for what technology allows them to do (or not to do). I therefore think the first question to be asked is: can the web do things better than an app (or, indeed, vice versa)? When you then start looking at what is being done (and what users may want to do if and when technology allows them to in a convenient and accessible way), you will come to a couple of easy conclusions.

Now, distinct to what old lore may have, users do not tend to care for technology much. They care for what technology allows them to do (or not to do). I therefore think the first question to be asked is: can the web do things better than an app (or, indeed, vice versa)? When you then start looking at what is being done (and what users may want to do if and when technology allows them to in a convenient and accessible way), you will come to a couple of easy conclusions. Prior to Google, people search through catalogues, and they thought that this was an awesome improvement over having to run to libraries and stuff in order to find things. Along come the Google fairies that deliver the same more easily and quickly, and everyone now feels that catalogues are a little quirky and very old-fashioned indeed.

Prior to Google, people search through catalogues, and they thought that this was an awesome improvement over having to run to libraries and stuff in order to find things. Along come the Google fairies that deliver the same more easily and quickly, and everyone now feels that catalogues are a little quirky and very old-fashioned indeed. It is a question of packaging and approach that will determine how well (or poorly) access and usage of content on any device works. If you call it an app or a widget or whatever else does not matter. Most people just do not care. They look at how easy it is to retrieve the latest weather forecast. If an app does that more quickly and comfortably, they’ll use that. If a widget does the same thing, they’ll choose what they like more. And if you can deliver the same thing as easily, as comfortably, as quickly and as discoverable on the web, they might just do that.

It is a question of packaging and approach that will determine how well (or poorly) access and usage of content on any device works. If you call it an app or a widget or whatever else does not matter. Most people just do not care. They look at how easy it is to retrieve the latest weather forecast. If an app does that more quickly and comfortably, they’ll use that. If a widget does the same thing, they’ll choose what they like more. And if you can deliver the same thing as easily, as comfortably, as quickly and as discoverable on the web, they might just do that. Currently, a device running constantly on a high-speed data connection sucks battery life. With an iPhone already running on something like 30 minutes when in full use (OK, I exaggerate, and, yes, I do know that Nokias do better – but then, they are not as usable [anymore]), this is a non-starter. People will not do it. Once this is solved (and this is a question of when, not of if), this goes away, and that will be a huge constraint removed.

Currently, a device running constantly on a high-speed data connection sucks battery life. With an iPhone already running on something like 30 minutes when in full use (OK, I exaggerate, and, yes, I do know that Nokias do better – but then, they are not as usable [anymore]), this is a non-starter. People will not do it. Once this is solved (and this is a question of when, not of if), this goes away, and that will be a huge constraint removed. Touch control is very much on the fore. And it makes perfect sense: that stylus just seems to dangle on the end of one (OK, normally two) of your limbs, it’s always on, it’s always with you (quite literally at arm’s reach) and you learn how to control it from pretty early on in life. Heck, it’s even been used to get us onto this earth in the first place (or so some people believe).

Touch control is very much on the fore. And it makes perfect sense: that stylus just seems to dangle on the end of one (OK, normally two) of your limbs, it’s always on, it’s always with you (quite literally at arm’s reach) and you learn how to control it from pretty early on in life. Heck, it’s even been used to get us onto this earth in the first place (or so some people believe). Last week, there was the

Last week, there was the  Upon the launch of the app store and the wondrous stories of the

Upon the launch of the app store and the wondrous stories of the  It is another question if these will be delivered via flexible widgets or larger, more comprehensive apps (functionally, a lot of apps effectively are covert widgets); this will simply be (and remain) a question on the complexity of any given task and the ease and superior (or not) delivery an app would provide over a browser-based service. There will be an equilibrium between the two but I posit that there will remain large areas where browser-based delivery will not be able to compete with specific applications (that will draw on data from the cloud as well). Incidentally, 58% of

It is another question if these will be delivered via flexible widgets or larger, more comprehensive apps (functionally, a lot of apps effectively are covert widgets); this will simply be (and remain) a question on the complexity of any given task and the ease and superior (or not) delivery an app would provide over a browser-based service. There will be an equilibrium between the two but I posit that there will remain large areas where browser-based delivery will not be able to compete with specific applications (that will draw on data from the cloud as well). Incidentally, 58% of