Last week, there was the Mobilebeat conference on, and – amongst many other things – a lot of guys felt they had to air their opinions on the future of mobile apps or, errh, no apps. They spoke so elaborately about it that even the revered FT (albeit in its blog section) and the BBC felt compelled to run stories. Amongst others, the CEO of “indie” app store Get Jar and Google’s wonderful Vic Gundotra, VP Engineering and also equipped with this most valleyed of all Silicon Valley job titles, i.e. “Evangelist” (I would really like one like this, too!), in his case for developers spoke about where they saw information and entertainment on mobile phones going in the future and how the ecosystem would look like.

Last week, there was the Mobilebeat conference on, and – amongst many other things – a lot of guys felt they had to air their opinions on the future of mobile apps or, errh, no apps. They spoke so elaborately about it that even the revered FT (albeit in its blog section) and the BBC felt compelled to run stories. Amongst others, the CEO of “indie” app store Get Jar and Google’s wonderful Vic Gundotra, VP Engineering and also equipped with this most valleyed of all Silicon Valley job titles, i.e. “Evangelist” (I would really like one like this, too!), in his case for developers spoke about where they saw information and entertainment on mobile phones going in the future and how the ecosystem would look like.

Now, let’s get serious.

What was Said?

First, GetJar‘s CEO sees the market for mobile applications becoming – get this – as big as the Internet (woah!). He then said also that it would peak at about 10m apps (in total?) by 2020. Hmm. GetJar then went on to warn that the number of developers would drop “drastically” and that only about 10% would be able to survive. The others would take their skills elsewhere. So where then? To the web? (This is of course interesting also because GetJar will deliver Sony Ericsson’s App Store…).

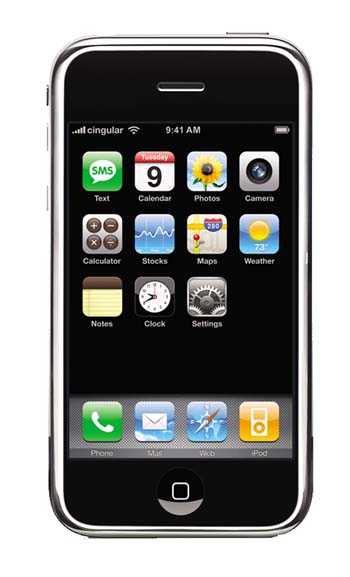

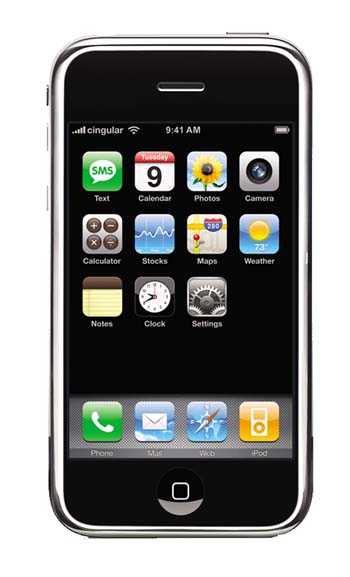

It is here where Google comes in. Gundotra said that, according to Google (and who would question them), the web had won. Even (!) Google was struggling with the device fragmentation in mobile and many, many applications could be delivered through “incredibly powerful” browsers as well. He even borrowed Steve Jobs for his argument, pointing out that the Apple CEO had announced that the iPhone was “Built for the Web” upon its launch.

There were others who contributed: Nokia’s Head of Services reminded everyone that Nokia was there to help with its Qt (Cutie, geddit?) cross-platform application network . The Symbian Foundation’s Executive Director, Lee Williams queried the need for more app stores and called, instead, for more than “just a bucket of apps”, which should look like an aisle with the very stuff that specific consumer is interested in and which (s)he could wander down at leisure.

They all however concluded that it [scil. the mobile web] was not there yet. Hm again… Let’s try to disentangle this all:

The Needle in the Haystack

Upon the launch of the app store and the wondrous stories of the iShoot developer Ethan Nicholas who coded in his bedroom after work only to resign from his day job weeks later because he made more money than he had ever thought. A lot of developers read that and, since it is the wet dream of every games developer (earn cash with an honest game without the “suits” fiddling with your game in between; anyone remember Copeland’s skateboarding turtle?), embarked on the journey themselves. And then they found, oops, it does not work that way? Why not? Well, because there are more than 400 applications going live every day. And with the sheer number of them, it could well be that the best app ever written is already out there but buried deep a couple of categories down in the app store.

Upon the launch of the app store and the wondrous stories of the iShoot developer Ethan Nicholas who coded in his bedroom after work only to resign from his day job weeks later because he made more money than he had ever thought. A lot of developers read that and, since it is the wet dream of every games developer (earn cash with an honest game without the “suits” fiddling with your game in between; anyone remember Copeland’s skateboarding turtle?), embarked on the journey themselves. And then they found, oops, it does not work that way? Why not? Well, because there are more than 400 applications going live every day. And with the sheer number of them, it could well be that the best app ever written is already out there but buried deep a couple of categories down in the app store.

This is no big surprise. It is how it works in any sector: one smart kid is not enough, you also need the environment and a lot of other building blocks to have a winner (as reigning F1 World Champion Lewis Hamilton is painfully realizing this year).

In the app store’s (and a gazillion other) case, this means that you have to make sure that you gain some attention. From Apple (or any other app store operator), from the press, from the users out there. And this is not news. There have been very well written pieces about this galore (see here for just one of them).

So will this mean the fall of a lot of the developers that went about their business thinking the app store magic would do away with centuries of business logic (there is a reason why companies have sales & marketing departments, you know…)? Yes, very probably. But does that mean the app model is flawed? No.

The Hit Dilemma

One of the Mobilebeat participants, namely Playfish, creators of some of the most successful Facebook games who released on the iPhone, too, complained about the hit-driven nature of games on the App Store. Whilst I am painfully aware of this dilemma, one has – again – to point out that this is pretty much how most of the economy works, too, unless, that is, one builds a superior and dominant brand (Tetris would be the example for the games world).

Other industries know this, too. Everyone knows IBM is a leading computer maker. Hardly anyone remembers that the Dutch electronics giant Philips used to be one of the biggest players in that market (not even Wikipedia mentions this); their CeBIT booth was bigger than IBM’s throughout the 70’s and early 80’s (my dad worked for Philips then; I need to dig out some pictures). What happened? Hey, they missed some crucial disruptive innovations and they were history…

What I want to say is that no one is immune to the demand for constant innovation and improvement (otherwise some Firefox will sneak around the corner and steal market share). The reason why this hit dilemma is more painful in mobile games than elsewhere is the relatively small size of the market to date: it is more difficult to build reserves than in other, more established sectors.

How Many App Stores? Mee too, me three, me four, …

With Apple’s roaring success with the app store, the whole industry stampeded to put out their own, and they have been moderately successful or failed. But it is early days! Why did they fail? Because they equally had hoped that one thing and one thing only (just name your bucket of apps an “app store”) would heal the painful failure of the sector in converting otherwise gladly paying users to also using, consuming, contributing to entertainment and information on their mobiles. Now, this overlooked that Apple’s model did not only consist of a storefront. It also consisted of a fairly simple developer programme (with a click-through agreement), a fair(er) revenue share to the developers and unprecedented ease of use in getting to the app of one’s choice. Try and apply this to, say, the launch of Nokia’s Ovi Store…

With Apple’s roaring success with the app store, the whole industry stampeded to put out their own, and they have been moderately successful or failed. But it is early days! Why did they fail? Because they equally had hoped that one thing and one thing only (just name your bucket of apps an “app store”) would heal the painful failure of the sector in converting otherwise gladly paying users to also using, consuming, contributing to entertainment and information on their mobiles. Now, this overlooked that Apple’s model did not only consist of a storefront. It also consisted of a fairly simple developer programme (with a click-through agreement), a fair(er) revenue share to the developers and unprecedented ease of use in getting to the app of one’s choice. Try and apply this to, say, the launch of Nokia’s Ovi Store…

So do users need more than one store? No, not in general. If you can get all you ever need, want or desire from one destination, you don’t need another one. This however becomes a little precarious with a view to monopolizing channels. You would never know if there are not some that are a little more equal than you… So, having Firefox, Chrome, Opera, etc. next to Internet Explorer did the world a ton of good. And having Nokia, Sony Ericsson, the carriers working on alternatives to Apple’s app store is arguably of equal value. Will the user care? It depends on the execution: Google’s superior search algorithms made the old-style catalogue model previously found in search engines superfluous; why do I need to sort something if I have a little fairy that races to get me what I want in no time? So: if I have a bucket that comes with a little fairy, I don’t need long, long supermarket aisles. I’d rather get it home-delivered by the search fairies.

It’s the Usability, stupid!

Now to the key question: separate apps or web? Now in Google’s case, their pleading is somewhat obvious: well, they would, wouldn’t they?

Google, on the other hand, has apps out on most platforms for most of their web services: Be it Gmail (great Blackberry app!), Maps, or – all in one – their iPhone Google app, it comes as an app. And why?

Because it would otherwise be unusable! OK, let me rephrase that: the delivery of browser-based applications through mobile phones suffers some very severe setbacks today, amongst which usability on a small screen, constant connectivity and bandwidth. Whilst the latter two are arguably solvable some time soon, the former is a little trickier: when delivering to a mobile device, you not only have to download all underlying data (graphical assets, etc) but also an interface that works on that device. And because of the small form factor of mobile phones (even in the case of large-screen touchscreen phones like the iPhone), this is likely that your user experience will be significantly worse than on a large screen equipped with mouse, touchpad, etc. Apps can bridge this usability gap, and I would argue that this is precisely why Google is producing them. The underlying content can often (not always) well be delivered from the cloud but the UI of small devices is crucial to their sensibility.

With both (mobile) browser technology and handsets improving, the space available for services that can sensibly (and with superior costs) be delivered from the cloud (i.e. through the web) will increase, and steeply. However, there will always be applications that will either be impossible to deliver via the web (name a high-end 3D racing game on the web) or where a specific mobile UI would greatly improve the usability of any service.

It is another question if these will be delivered via flexible widgets or larger, more comprehensive apps (functionally, a lot of apps effectively are covert widgets); this will simply be (and remain) a question on the complexity of any given task and the ease and superior (or not) delivery an app would provide over a browser-based service. There will be an equilibrium between the two but I posit that there will remain large areas where browser-based delivery will not be able to compete with specific applications (that will draw on data from the cloud as well). Incidentally, 58% of Wired readers agree with me (and another 17% don’t care; check the bottom of the article) 😉

It is another question if these will be delivered via flexible widgets or larger, more comprehensive apps (functionally, a lot of apps effectively are covert widgets); this will simply be (and remain) a question on the complexity of any given task and the ease and superior (or not) delivery an app would provide over a browser-based service. There will be an equilibrium between the two but I posit that there will remain large areas where browser-based delivery will not be able to compete with specific applications (that will draw on data from the cloud as well). Incidentally, 58% of Wired readers agree with me (and another 17% don’t care; check the bottom of the article) 😉

This can be seen on the (“normal”) web, too: Google Docs (Google’s online suite of office applications) is, despite a lot of effort and being free to use, an utter underdog to MS Office or Open Office (the only numbers I could find give Google Docs a market share of between 1% and 5%). It is, I think, because downloadable office “apps” are so much more usable (and react instantaneously irrespective of my ISP’s moods) than online services. The complexity of the computing (and – more importantly – the bandwidth necessary to deliver it) is just too overwhelming (see here for a previous post on this).

More evolved mobile apps often are (and/or will be) a hybrid: they offer a front-end that optimizes the data drawn from an online environment for use on a specific mobile device. It will not be an “either/or” but an “and”. Anything else would anyway be so last century!

In Conclusio:

Whenever possible, services will move online because it is cheaper to produce. Whenever necessary, they will be delivered through dedicated apps because it is required to use them!

Last week, there was the

Last week, there was the  Upon the launch of the app store and the wondrous stories of the

Upon the launch of the app store and the wondrous stories of the  It is another question if these will be delivered via flexible widgets or larger, more comprehensive apps (functionally, a lot of apps effectively are covert widgets); this will simply be (and remain) a question on the complexity of any given task and the ease and superior (or not) delivery an app would provide over a browser-based service. There will be an equilibrium between the two but I posit that there will remain large areas where browser-based delivery will not be able to compete with specific applications (that will draw on data from the cloud as well). Incidentally, 58% of

It is another question if these will be delivered via flexible widgets or larger, more comprehensive apps (functionally, a lot of apps effectively are covert widgets); this will simply be (and remain) a question on the complexity of any given task and the ease and superior (or not) delivery an app would provide over a browser-based service. There will be an equilibrium between the two but I posit that there will remain large areas where browser-based delivery will not be able to compete with specific applications (that will draw on data from the cloud as well). Incidentally, 58% of  Everyone with an iPhone will by now have seen and “played” them: the first generation of multi-player games where most of the computing is done in the cloud, relieving the handset from such labourious tasks. This, according to

Everyone with an iPhone will by now have seen and “played” them: the first generation of multi-player games where most of the computing is done in the cloud, relieving the handset from such labourious tasks. This, according to  So, will it work? The report points out iPhone apps for the likes of Amazon, eBay, etc and, yes, for such apps I am sure it will work: they basically extend a front-end of a web service to a mobile device. The “app” is basically a client that facilitates input and serves as a crutch for the smaller screen where it is necessary to optimise the available data so as not to overburden the little available space with non-core information.

So, will it work? The report points out iPhone apps for the likes of Amazon, eBay, etc and, yes, for such apps I am sure it will work: they basically extend a front-end of a web service to a mobile device. The “app” is basically a client that facilitates input and serves as a crutch for the smaller screen where it is necessary to optimise the available data so as not to overburden the little available space with non-core information.